I’d love to share an experience from a few years ago that illuminates how facilitative leadership was used to weave alignment and transform culture and relationships.

I was consulting with a large corporation where conflict and tensions were brewing among senior management in three main areas of the organization. Their teams were feeling pressures from an increasingly complex and demanding marketplace. The accelerating need for innovation brought new internal stressors, and conflicts were growing hotter and more frequent.

Signs of poor collaboration showed up as projects dragging on without closure, people avoiding or withholding information in meetings and back channeling to influence decisions, and confusion about who needed to be involved in what. There was a general sense of powerlessness, a belief that unless you had the ear of your VP, you would not be able to resolve minor conflicts.

No one was happy. There was a widespread frustration with the status quo.

My first priority was to spend time learning about what was really going on. I started by engaging some key influencers from across the organization in simple conversations, creating rapport and asking questions, listening, and reflecting. I started to get a preliminary idea of the current situation from the point of view of each area.

I worked with three main groups: operations, marketing, and IT, each of which had their unique circumstances. For example, the operational group was primarily concerned with quality and consistency. They felt accountable to staying within budget and maintaining a realistic scope, given the available resources. They saw planning as foundational, because it enabled quality performance that was measured in daily reports and variances. Their focus was more on the human side of operations than on technology.

The marketing group, on the other hand, had a keen and energized focus on innovation and being responsive to customers. They were tracking not so much consistency, as the operations teams were, but the deliverability in service to customers’ needs and desires.

Finally, the technology group had a longer-term view. They were focused on strategically investing in resources that would pay off over time. They wanted to be deliberate in thinking through the future implications of changes and adaptations being made in the present.

These different time orientations affected where each group focused their energy, attention and decision-making. This created conditions for competing interests and more than a sense of working at cross-purposes.

I sought to understand the perspectives of additional key people in these various groups, through interviews, over coffee, or via asynchronous back-and-forth communication. I asked questions, sought their feedback, and used shared artifacts to track our communication, emerging mental models and insights (often on the back of napkins). I also considered different personality styles and orientations that affect collaboration and relationships, for example, introversion and extroversion, and factors that shaped group and intergroup identity.

For example, I found that the best way to work with marketing was face to face. In group meetings, a ‘hive mind’ would emerge as they discussed issues with great clarity and enthusiasm. By contrast, the operations teams worked better with more stability and consistency, with well-planned, structured meetings. Meanwhile, the tech group more fluidly engaged via threaded email conversations than with live group conversations.

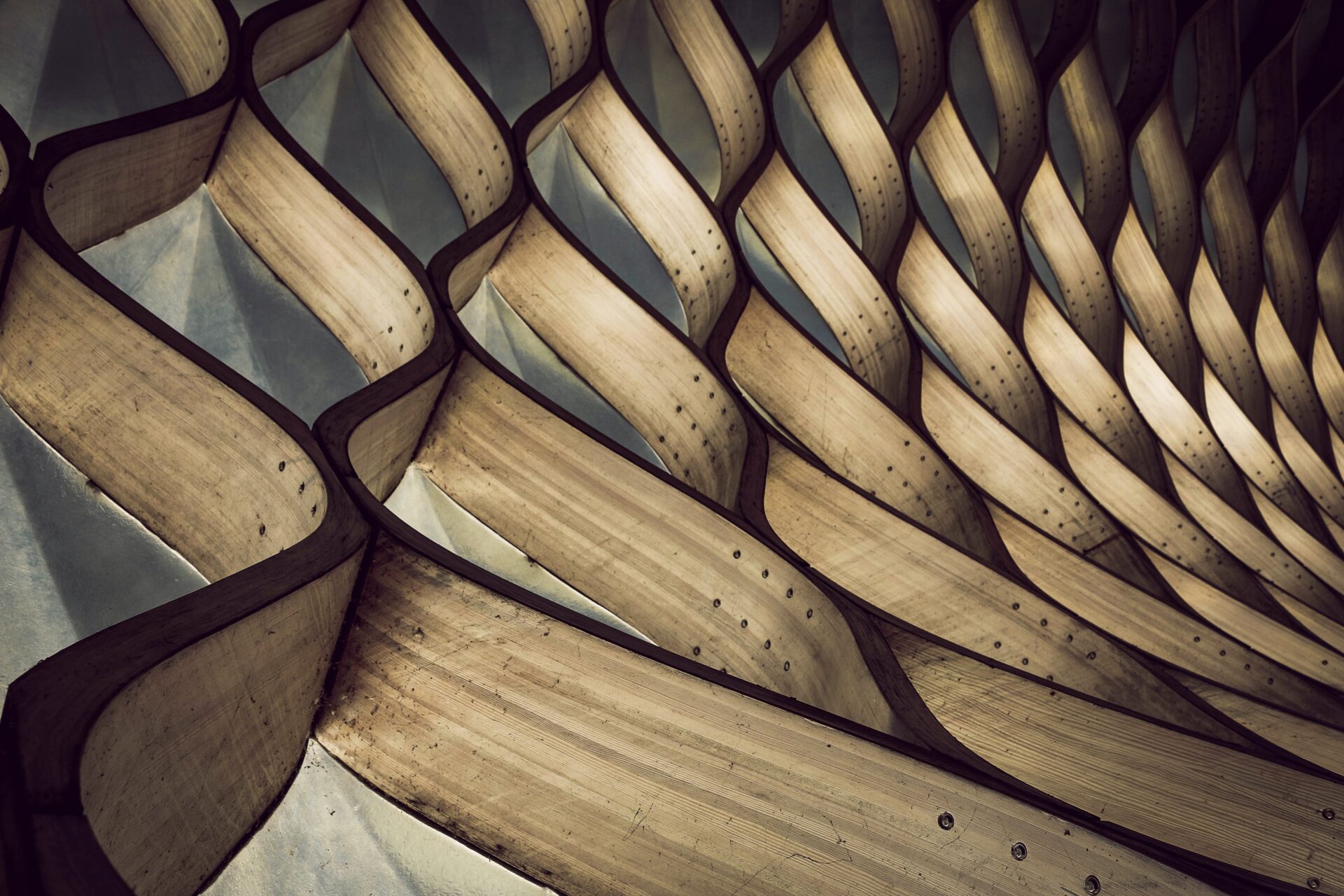

My next priority was to seed new perspectives for a collective sense of what was really going on. The work of weaving these diverse orientations meant supporting each group to see itself as a larger whole, while also learning more about the unique pressures and opportunities of the other groups. And that meant concurrently addressing group dynamics and the collective ability to be more constructive within tension. We were striking out into new territory that welcomed care, challenge, depth and authenticity.

As I began to bring groups together, I would ask group members to take perspectives on themselves, and on the views of the other two groups. I supported them to reflect back the values, interests and priorities they were hearing. This helped the person reflecting to recognize old biases and become more neutral and objective, in part, because they had support to find a way to converse outside of the interpersonal dynamics that governed their day-to-day interactions.

I also invited people to reflect on and share where they saw possibilities, as well as the limitations of others’ points of view. The safety of these facilitated conversations also created space for groups to be more forthcoming about their own limitations and opportunities to improve.

It was also important to separate out these inquiries – to consciously include “self and other” to isolate the elements where they needed to find more of a sense of togetherness.

Dropping defences, listening, along with expressing and offering feedback were crucial.

The core idea is that everything that we perceive, (in our selves, in our relationships, in this room, in the world) – is a reflection of our way of seeing and being, is here for our learning, and has something worthwhile to offer.

By allowing each group to have their distinct sovereign perspective, clarified and expressed fully, and by supporting a neutral stance outside the heat of interpersonal conflict, where we could demonstrate a more tangible understanding of each others’ realities, we started to see two new perspectives emerge.

One was a universal sense of alignment, in spite of their individual circumstances.

Of course, each person was clear that their wants and needs were in a different territory from the other groups, because they had very legitimate, distinct responsibilities. Technology needed to make thoughtful investments, with the appropriate tech in place with the right architecture and infrastructure, all in line with best practices. Marketing was much more concerned about maintaining customer responsiveness and finding those new ways of value creation and consistent quality – because the reputation of the company was conveyed through them.

But while each of these stances was unique, there was a common realization that they were all contributing to the overall organization.

So through this process, groups began to appreciate not only their own value, but that of the other groups as well. This shared sense of how they all contributed to the organization’s larger mission came with a growing recognition of the power and creativity this aligned view afforded them that hadn’t been fully experienced before.

The second perspective that emerged was how each individual and group saw the world: the often invisible worldviews that we often see, and defend, as ‘the truth’.

‘The truth’ included the attitudes and values that they were subtly imposing on each other. When we started to unpack these assumptions and expectations, people began to notice the constraints of the other groups based on their priorities, structures, legal requirements, and commitments in the marketplace to which they were committed or bound.

These conversations helped introduce a new curiosity and appetite for learning, for strategizing in a more integrated way, and an increased willingness to listen and communicate more effectively. These new ways centered on the capacity of the collective rather than on hierarchy and function. Facilitative leadership grew the ability to collaborate beyond the fixed hierarchies into more adaptive and agile ways.

It became clear that a shared understanding about how things worked within the larger organization – including limits and possibilities – would support value creation and realignment.

We created new opportunities to collaborate that included not just listening, but deeply appreciating and empathizing with the underlying perspectives and needs that others were speaking from.

It highlighted how misalignment is often personal and interpersonal, and how investing in alignment can counter ossification, uproot outdated beliefs and help shape new possibilities.

Attuning to this deeper context supported the deepening of trust, and fuelled a desire for collective sensemaking and more integrated strategy-making. This created a shift in the tone of the meetings and the culture, and the telltale signs of a facilitative leader’s influence: a greater sense of belonging, more caring connection across functions and differences, and generative collaboration. The most durable and powerful impact is that the organization gained a new capacity to continue to weave alignment.

The more we zero in on the relationships between people and culture, and the more we can apply our facilitative leadership skills such as deep listening, asking great questions, and safely exploring differences, the more transformative our work will be as alignment weavers.

By creating opportunities and skills to appreciate both shared aspirations as well as the unique underlying needs of other teams, culture becomes more collaborative, robust and responsive, even within the confines of challenging structural limitations.

Finally, by building broad capacity for these skills, organizations are able to grow, adapt and evolve as they move into increasingly dynamic and complex times.

________________________________________________________

At Ten Directions, we’ve dedicated the last ten years in growing the world’s premier developmental path for facilitative leadership, the Integral Facilitator® certificate path. We develop leaders and facilitators who can recognize, invite in and engage more perspectives, more depth, and more complexity and weave alignment across differences. To find out more about the Integral Facilitator® certificate path and other developmental opportunities for agility in leadership, visit us at tendirections.com.